By John Halford, Bindmans LLP [22 April 2016]

John Halford, Bindmans LLP [22 April 2016]

Introduction

1. On 11 December 1948, British troops entered and took control of the rubber tapping plantation village of Batang Kali, Selangor in what was then Malaya. They separated the women and men and, after shooting one man, began a series of interrogations to establish whether the remaining villagers were supporting Communist insurgents. Many villagers were subjected to mock executions. The following morning the women, children and one man were put on a truck. The troops then escorted 23 of the men out from the longhut where they had been held overnight and, within minutes, every one had been shot dead. This incident is known as the Batang Kali Massacre (or ‘the British My Lai’). No-one has ever been prosecuted for it. The British government has never apologised, acknowledged fault or made any form of reparations. When challenged, it denied legal responsibility for the killings, despite Malaya then being a British Protected State, all Malayan nationals being British subjects and the troops involved being British, deployed on the instructions of the British Cabinet to protect British interests in the rubber trade.

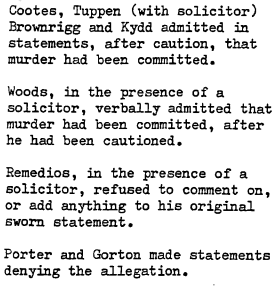

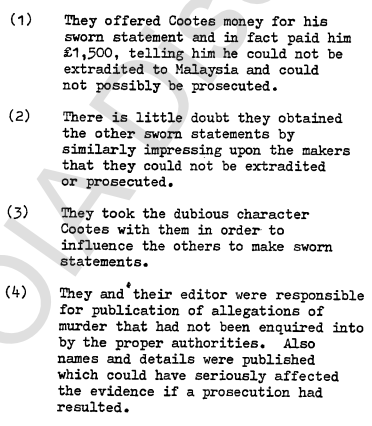

2. The killings were portrayed as a military victory at the time, but in 1970 six of the soldiers involved presented themselves, first to the press and then to the Metropolitan Police, to confess that they had murdered the male villagers. The resulting police investigation was terminated prematurely by the government against the wishes of the officers involved who described the reasons as “political”. The bodies were not exhumed and those in command at Batang Kali were never interviewed as that had been planned as the final stage of the investigation. In 1993, a Malaysian police investigation began, but was also blocked by the British government.

3. Then, in 2008, a campaign began in Malaysia to press for a British public inquiry into what had happened and its cover-up. The inquiry was refused by the government in 2010, a decision then challenged in judicial review proceedings brought by family members of those killed, R (Keyu and others) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs and another. The claim was refused by the Divisional Court , the Court of Appeal and, on 25 November 2015, by the Supreme Court . Only a positive ruling by the European Court of Human Rights, to which the victims’ families now turn, could now secure a public inquiry.

4. So, subject to what happens in Strasbourg, is the Batang Kali case now simply to be consigned to legal history as an unsuccessful and “thoroughly stale” claim, which is how it was described by Treasury Counsel Jonathan Crow QC in the Supreme Court?

5. Or perhaps it should be remembered more charitably as an “honourable crusade” which could not succeed because, as Lord Kerr thought (see para 285 of his Supreme Court judgment):

“[t]his is an instance where the law has proved itself unable to respond positively to the demand that there be redress for the historical wrong that the appellants so passionately believe has been perpetrated on them and their relatives. That may reflect a deficiency in our system of law.”

6. This note suggests that neither should be the epitaph of the case, that it will be remembered for very much more and that the three courts’ orders are certainly no reflection of the true outcome.

First Reason – Law: temporal scope of Art 2 ECHR

7. First, Keyu raised important and far reaching questions about the retrospectivity of the UK’s international human rights obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights (‘ECHR‘) and, to the extent they are retrospective, their domestic enforceability through the Human Rights Act 1998 (‘HRA’). The answers did not help the families of those killed at Batang Kali, but they are likely to help others when new evidence comes to light of serious past wrongdoing.

8. The families’ Art 2 case was built on Šilih v Slovenia (2009) 49 EHRR 996, Janowiec v Russia (2013) 58 EHRR 792, Brecknell v United Kingdom (2007) 46 EHRR 957 and Harrison v United Kingdom (2014) 59 EHRR SE 1 as follows.

9. First, it was now settled law that Art 2 creates an autonomous and detachable duty to investigate deaths occurring in suspicious circumstances.

10. Secondly, the Convention demanded investigation of deaths occurring before the “critical date” when the relevant state’s Convention obligations first arose, where relevant acts or omissions had occurred after the critical date and there was a genuine connection between the death and the critical date, normally the passage of no more than ten years between those dates. If the critical date was 1953, when the United Kingdom had signed up to the Convention and extended it to Malaya, just five years after the killings, then the genuine connection criterion was met and so, given all investigations up until then had been defective (indeed cover ups) the Art 2 investigatory obligation was activated in 1969 when compelling new evidence that the killings were unlawful came to light through the soldiers’ confessions.

11. The framework was accepted to be legally correct by the majority of the Supreme Court. They also accepted there was new, weighty and compelling that came to light in 1969. However, with the exception of Baroness Hale they did not accept the critical date was 1953, and held it was 1966, when the United Kingdom had first recognised the right of individual petition to the ECtHR. It followed that the deaths had occurred more than ten years before the critical date and so the connection was insufficient.

12. It is difficult to reconcile the Court’s majority decision with the international law principle that a treaty becomes binding as soon as it is ratified. But the effect of the decision is that suspicious deaths that occurred between 1966 and 1976 will meet the genuine connection criterion and so if sufficiently weighty and compelling new evidence now comes to light about them the Art 2 investigative duty will be activated. This potentially could embrace many killings in Northern Ireland, especially those falsely presented as sectarian killings.

13. It is important to sound two cautionary notes, however. First, the majority in the Supreme Court went on to hold that, even if the genuine connection test had been met, the Batang Kali families may have waited too long to enforce the investigatory duty. Lord Neuberger’s view was that the legal challenge ought to have been brought in response to the abandonment of the 1970 investigation, presumably by way of a petition to Strasbourg within a year of that date.

14. Secondly, the majority decided not to determine whether In re McKerr [2004] 1 WLR 807 remained good law on the question of the retrospective application of the HRA. In that case the House of Lords had held that there was no “ancillary right to an investigation of [a] death [of] a person who died before the Act came into force” except where an investigation had already begun but had yet to be concluded at that date. This was questioned in In re McCaughey (Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission intervening) [2012] 1 AC 725 and sits uncomfortably with the statutory purpose of the HRA which is to ensure that ECHR obligations are mirrored in domestic law. This question will need to be resolved in a future case.

Second Reason – Law: the door remains ajar on proportionality

15. In the event their international law arguments failed, the Batang Kali families had an alternative position which was that, tested to the exacting standards of proportionality, exercise of discretion to refuse an inquiry was unjustifiable. For this argument to succeed, they had to establish that proportionality replaced Wednesbury as the standard for justification for discretionary decisions in cases involving fundamental interests including the common law’s demand for an adequate explanation of deaths of detained persons which could be traced back to Coke’s, Second Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (1642) p.52 and The Mirror of Justices, attributed to Andrew Horn (1305-1328), pp.30-31..

16. The Supreme Court declined to reach a decision on whether proportionality was now the proper standard of review, with the majority adding that this would be inappropriate for a five-Justice court. In the majority’s view, the result of the case would be the same regardless of whether the Respondents’ decisions were assessed to a proportionality or Wednesbury standard. Notwithstanding that, each edged a little closer to accepting proportionality was the way forward for the common law. Like Kennedy v Information Commissioner [2015] AC and Pham v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] 1 WLR 1591, Keyu will be an important paving stone in that path.

Third Reason – Law: Lady Hale’s dissent on rationality and the Divisional Court’s public interest factors

17. There are only two cases in which refusal to establish a public inquiry has been successfully challenged on conventional public law grounds (as opposed to HRA-based ones): Kennedy and Black v Lord Advocate 2008 SLT 195 and R (Litvinenko) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] EWHC 194 (Admin).

18. For Lady Hale, Keyu should have been the third. Her powerful dissent sets out why, in her view, public and family interests were insufficiently weighed in the balance when discretion was exercised to refuse the inquiry the families sought. It merits very careful consideration for those drafting representations to decision-makers arguing for positive exercises of the same discretion more recent deaths as does the Divisional Court’s discussion of the public interest factors to be taken into account when such a decision is made (see paragraphs 157-175 of their judgment).

Fourth Reason – Law: responsibility reflects military reality

19. As mentioned above, one of the most extraordinary features of the Keyu litigation was the persistent denial of legal responsibility for the killings by the Respondents. They argued that in 1948 British troops in Malaya were legally the responsibility of either the Sultan of Selangor, or the Federal Administration, which was appointed by the Crown but semiautonomous. Either way, they argued, legal responsibility passed to the state of Malaysia upon independence.

20. Like the Divisional Court and Court of Appeal before it, the Supreme Court was having none of this sophistry and on this issue the Justices were unanimous. Under the pre- independence constitutional arrangements, the UK had been in complete control of the defence and external affairs of the State of Selangor and the Federation of Malaya. The British Army, while on active service there, had remained His Majesty’s forces under the command of the Crown exercised through the Army Council in accordance with the King’s Regulations. The Army had been deployed to further UK interests, pursuant to a command structure and orders that could be traced up to the Cabinet. Those killed at Batang Kali had been in the control of the British Army and so within UK’s jurisdiction. The grant of independence in 1957 did not transfer liabilities and obligations in respect of the deaths.

21. Keyu is a ringing endorsement of the reality of military command structures and the fact that legal liability responsibility should mirror them.

Fifth Reason – Facts: innocence

22. In 1948 and early 1949 the official account of the killings was that ‘bandits’ (a euphemism for Communists insurgents) had been lawfully unnecessarily killed in the course of a pre-planned escape attempt and that “a large quantity of ammunition had been found under a mattress”. Internal army memoranda observed that such villages were often rubber tappers by day and ‘bandits’ by night. The official account was repeated in Parliament by ministers, and adopted in the official history of the Scots Guards regiment to which the British troops belonged (“[s]uffice to say that those killed were active bandit sympathizers”).

23. When the campaign first was launched, the government responded by asserting that there was no reason to question the outcome of the past investigations and so none was reopen or otherwise investigate. When the final refusal decision was litigated, the position was being taken that it was near-impossible to reach conclusions about what had happened.

24. The Divisional Court saw things differently. On the basis of the available documents, it felt itself able to state:

“…there is no evidence, 63 years later, on which any of the 10 key facts relating to what happened at Batang Kali can seriously be disputed. It is therefore both helpful and necessary to an understanding of what happened after the deaths to set the 10 facts out.”

25. Those indisputable facts included that:

“i) Batang Kali was a village on a rubber plantation, inhabited by families. They did not wear uniforms, had no weapons and were a range of ages….

v) Interrogation of the inhabitants took place. There were simulated executions to frighten them, causing trauma.

ix) The hut with 23 men was unlocked. Within minutes all of the 23 men were dead as a result of being shot by the patrol.

x) The inhabitants’ huts were then burned down and the patrol returned to its base.”

25. By the Supreme Court stage, these and many more important facts had been agreed, enabling the Justices to add their own gloss to them. Lord Kerr and Lady Hale, for example, felt able to note the apparent innocence of those killed. This was hugely important for their family members, given the significance in Chinese culture of ancestral honour. The stigmatising way their family members have been described was finally mitigated

Sixth Reason – Facts: guilt

26. The Supreme Court did not stop there, however. Lord Neuberger recognised at paragraph 137 of his speech:

“[i]t is not as if the appellants have got nowhere: in these proceedings, the Divisional Court, the Court of Appeal and now this court have all said in terms that the official UK Government case as to the circumstances of the Killings may well not be correct and that the Killings may well have been unlawful.”

and at paragraph 111 he observed that, by 1969 and 1970 there was “evidence available to support the notion that they were unlawful and may have amounted to a war crime”.

27. Lord Kerr felt able to go even further at paragraph 204:

“The shocking circumstances in which, according to the overwhelming preponderance of currently available evidence, wholly innocent men were mercilessly murdered and the failure of the authorities of this state to conduct an effective inquiry into their deaths have been comprehensively reviewed by Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury PSC in his judgment and require no further emphasis or repetition. It is necessary to keep those circumstances and that history firmly in mind, however, in deciding how our system of law should react to the demand of the relatives of those killed that the injustice that has been perpetrated should be acknowledged and accepted.”

Seven Reason – Costs: when justice demands a special costs order

28. Very occasionally, the courts will recognise that it is not in the interests of justice to award costs against an unsuccessful litigant in a public interest case. Even more rarely still, such a litigant who has succeeded on certain issues, but not secured the remedy they seek, will recover some of their costs.

29. In Keyu, in each stage the Defendants/Respondents sought costs against the Claimants/Appellants and indicated they were minded to enforce any order made. The Courts were unimpressed. No order for costs was made at any level. The Divisional Court went further still unexplained why not in a supplementary judgement:

“…looking at the overall justice of the case, we do not think it would either be right or fair to make an order that the claimants pay the costs of the Secretaries of State. The amounts to which the claimants would in reality be exposed might be quite substantial and in the light of the history of this matter set out in our judgment visiting on them a consequence in costs would be unjust”

Conclusion: judicial review as a truth-revealing process

30. Most student textbooks, and not a few judgments, will tell the reader that judicial review cases are about law not facts – that the search is for legal truth only. Keyu tells a different story, one in which the Courts, whilst unwilling to further legal remedy sought, refused to be complicit in this suppression of the truth which the respondents had so effectively perpetrated for six decades. This was a judicial review claim that prompted every judge who heard it to exonerate the victims of the killings, the majority of the Supreme Court to note, in understated terms, that a war crime may well have been committed, and one of their number, Lord Kerr, to make comments that go beyond the findings of many public enquiries into similar incidents.

31. Whether there will be state acknowledgement and acceptance of what happened beyond the judiciary remains to be seen. But it is their words that now overwrite the wholly false explanation offered up until now by the state for what happened at Batang Kali.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a comment »